In the August issue of HE Admissions Insights, our international survey on key competencies for academic success ranked critical thinking as the #1 competency across disciplines. Critical thinking has been mentioned frequently in recent years—by universities, employers, and policymakers. It is also included in lists of “future skills”. That raises practical follow-up questions for admissions and program leaders: what exactly is critical thinking, how can we measure it, and can we develop it?

What is critical thinking?

There are several definitions of the term. A comparison shows that it typically includes cognitive abilities such as reasoning and quantitative problem solving, as well as several of the following aspects:

- Metacognition, i.e., reflecting on one’s own thought processes

- Motivation, dispositions, and attitudes, such as openness and curiosity, and the willingness to examine conclusions critically, question authority, and invest mental effort

- Problem-solving techniques, for example for reasoning, searching for and evaluating information, or analysing numbers, data, and facts

Critical thinking is therefore an interplay of cognitive abilities, metacognition, motivation, and problem-solving techniques that enables reasoned judgement and reduces biases.

Where does “critical thinking” come from?

People have been concerned with critical thinking for a long time, particularly in philosophy. Socrates explored how insights can be gained through structured dialogue, an early form of problem-solving. Enlightenment thinkers such as Immanuel Kant (1784) emphasized the motivational dimension of critical thinking: the courage to use one’s own understanding rather than relying on authority.

The term critical thinking became prominent in the 20th century. John Dewey (1910) introduced it as an educational objective—promoting scientific thinking in everyday situations. Edward Glaser (1941) framed it as part of problem-solving ability and helped establish the concept in psychological research. In practice, critical thinking—whether explicitly named or not—has always been a core element of scientific education at universities.

Why is critical thinking so important today?

The ability to analyse information and draw warranted conclusions has always mattered. So why do we increasingly call it a future skill? Because in several domains, the volume, speed, and strategic manipulation of information have changed the environment in which decisions are made:

- Work and leadership: decision-makers must analyze large amounts of sometimes contradictory information. Data-driven reasoning is often essential, and simple rules of thumb are frequently insufficient.

- Health behaviour: medical information is more complex, while misinformation and pseudo-medical advice can cause harm, spread quickly and even influence political decision makers.

- Democracy: online ecosystems (social media, AI-generated content) amplify misinformation and propaganda, increasing the need to evaluate claims and evidence carefully.

Critical thinking and its opponents

Critical thinking is inconvenient for authoritarian actors who benefit from manipulation and populism. They try to undermine fact-based reasoning—by attacking, intimidating or controlling media and education institutions, or by creating uncertainty around evidence. This makes critical thinking not only an academic goal, but also a form of societal resilience.

How can critical thinking be measured?

Several tests have been developed to measure critical thinking, focusing on different components. Butler (2024) provides an overview. Some instruments focus primarily on cognitive skills and resemble study aptitude tests in that they use complex problem-solving tasks and assess reasoning and quantitative skills.

- The California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST) assesses skills such as quantitative reasoning, deduction, problem analysis, and argument evaluation. Results tend to correlate strongly with study aptitude tests as GRE and academic performance.

- Similar assessments include the Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment (HCTA), the Cornell Critical Thinking Test (CCTT), and the Watson–Glaser™ II Critical Thinking Appraisal, which also assess reasoning skills and correlate (to varying degrees) with intelligence and study aptitude measures.

- Other instruments, such as the California Measure of Mental Motivation (CM3) or the California Critical Thinking Dispositions Inventory (CCTDI), focus more on motivational aspects. These also correlate with academic outcomes, but less strongly than cognitive tests.

As observed, certain critical thinking assessments exhibit high correlations with study aptitude tests, suggesting that these tests measure critical thinking abilities to a significant extent.

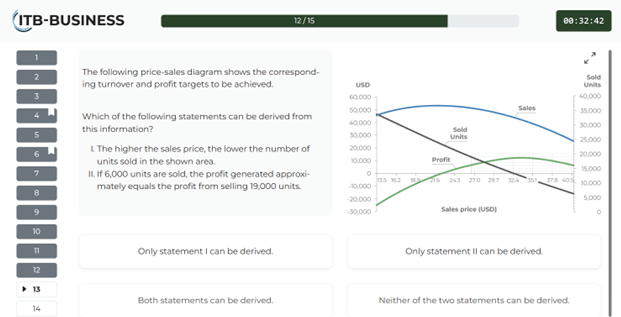

One task format that measures critical thinking and appears since the 1980s in aptitude tests for economics, business administration, and science, is called “Graphs and Tables” or “Interpreting Charts”. Test-takers receive numerical information (sometimes discipline-specific, sometimes interdisciplinary) plus an explanatory text, and then must judge whether statements are supported by the data. Importantly, some statements may feel highly plausible but are not supported by the information given. The figure shows a Graphs & Tables item of an ITB-Business prep test.

Similar task formats were introduced in 2010 in the Graduate Test for Economics, Business and Social Sciences (GTEBS) and in 2012 in the Graduate Management Admission Test (GMAT). Performance in such tasks is a meaningful predictor of academic success.

Can critical thinking be improved?

Many components of critical thinking can be trained. While general cognitive ability is relatively stable in adulthood, metacognition can be strengthened, and problem-solving techniques can be learned and improved with practice. Dispositions such as intellectual humility and openness can also be shaped—especially when learning environments reward evidence-seeking and revision of views.

Practical pathways include:

- Higher education itself: research methods, statistics, logic, academic writing, and scientific reasoning.

- Targeted courses and workshops: especially useful for those who need development without completing a full degree program.

- Books and columns: e.g., Paul & Elder’s The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking (practical checklists, easy to read) and Amanda Ruggeri’s BBC column How Not to Be Manipulated.

- Deliberate information habits: reading across viewpoints, checking primary sources, seeking counterarguments, and separating plausibility from evidence.

Conclusion

Critical thinking is not one single skill. It combines cognitive abilities, metacognition, dispositions, and problem-solving techniques. It is not new, but becoming more important in a complex, data-rich, and misinformation-prone world. That is why it is rightly described as a future skill.

Further reading

- Butler, H. A. (2024). Predicting Everyday Critical Thinking: A Review of Critical Thinking Assessments. Journal of Intelligence, 12(2), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence12020016

- Glaser, E. M. (1941). An experiment in the development of critical thinking. Teachers College, Columbia University

- Kant, I. (1784). Beantwortung der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung? Berlinische Monatsschrift, 4, 481–484.

- Ruggeri, A. (2024). How Not to Be Manipulated. BBC Future. https://www.bbc.com/future/columns/how-not-to-be-manipulated